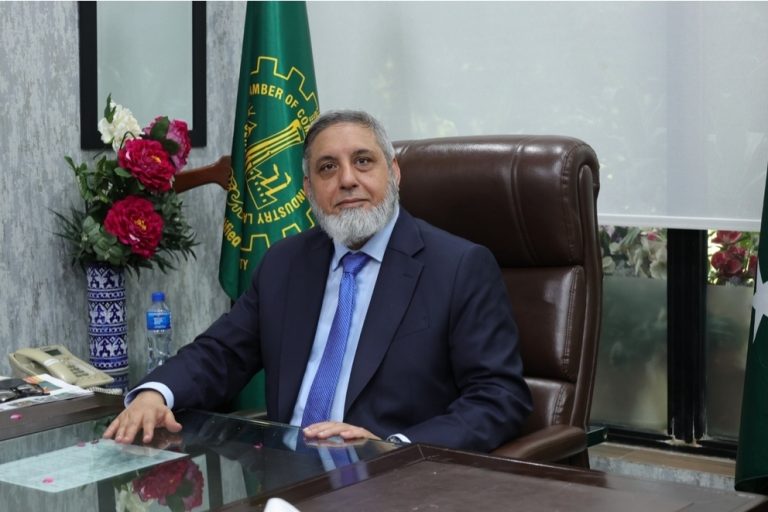

By Mian Abuzar Shad

President

Lahore Chamber of Commerce and Industry

In Islamic history, rose water has traditionally been used for cleansing sacred places or for the ritual washing of the deceased. But in a city like Lahore, where streets are filled with filth, washing roads with rose water—what kind of thinking does that reflect?

Read also: Businessman’s factory seized by criminal gang: LCCI President demands protection for industrialists

Is it not an insult to the public—who do not even have access to clean drinking water—that their taxes are spent on buying rose water to wash roads? Is this symbolic cleanliness just for media photo opportunities, or a display of a superiority complex?

Pakistan is not a country short on resources. However, the distribution and use of these resources have long been sacrificed for the interests of the powerful elite. Today, as the nation groans under the weight of inflation, unemployment, and heavy taxation, some fundamental questions demand urgent answers from those in power.

It is common knowledge that when ordinary citizens are struggling to pay electricity bills, buy medicines, or afford their children’s school fees, the billions worth of properties owned by Pakistani individuals in cities like London, Dubai, and New York raise serious questions:

Were these properties bought through legitimate means?

Were taxes paid in Pakistan on these assets?

Are NAB, FBR, and other institutions willfully silent—or simply helpless?

In Pakistan’s energy sector, the most expensive game is being played through Independent Power Producers (IPPs). The agreements signed with them not only burden the nation with debt but are so exploitative that payments are made even when no electricity is produced. Were these contracts signed in the national interest—or to fill the coffers of certain families, politicians, and the elite?

When farmers demand a fair price for their crops, the government claims the treasury is empty. Yet, on the other hand, mafias artificially inflate the prices of sugar, flour, cotton, and steel to reap billions—and no one holds them accountable. Are these mafias not connected to ministers, advisers, parliamentarians, and political dynasties? Has any serious action ever been taken against them?

Water scarcity has become a national security issue for Pakistan, but the construction of major dams is constantly stalled due to political disputes, legal entanglements, or internal resistance. Are there powerful groups opposing dam construction because their personal interests would be affected? Every year during monsoon, we face devastation through floods—followed by droughts. Are those blocking dam projects not national criminals?

In Pakistan’s political history, there are numerous events where key political figures seem to have ties to foreign institutions or individuals, having undergone media management and ideological grooming abroad. Can we truly say that their narratives and decisions are in Pakistan’s interest?

In Islamic tradition, rose water has long been reserved for sacred rituals, but in Lahore—where the streets are filthy—washing roads with rose water reflects a troubling mindset. It is humiliating for the public to be denied clean drinking water while their tax money is spent perfuming the streets. Is this symbolic cleaning just for the cameras—or an expression of elitist detachment?

All these questions point toward the need for deep and serious accountability. The nation demands real answers now. Statements, commissions, and committees will no longer suffice. If Pakistan is to be saved—if we are to leave behind a worthwhile country for the next generation—these questions must be answered. Otherwise, the day will come when the people will no longer ask questions—they will deliver judgment.