By Mushtaq A Sarwar

In Pakistan, the process of economic policymaking increasingly appears detached from ground realities and devoid of meaningful consultation with those who actually drive the economy—traders, industrialists, and tax professionals. The recently introduced Finance Act 2025 has only deepened the sense of alienation within the business community. Instead of bringing relief or reform, the new legislation—particularly controversial clauses 37A and 37B—has stirred unrest, triggering widespread concerns over unchecked powers granted to the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), including the authority to detain individuals without judicial oversight.

Read also: Pakistan-Azerbaijan: New avenues of brotherhood

When policies are formed in isolation, devoid of stakeholder dialogue, a dangerous trust deficit emerges between the state and the business class. The Finance Act 2025 is a reflection of this growing divide. By equipping the bureaucracy with sweeping powers—enabling arrests without court warrants and entangling small and medium enterprises in opaque digital systems—the state appears more focused on control than on cultivating trust.

These amendments are not mere technical revisions. They represent a broader shift in governance, where surveillance overtakes transparency, and unilateral decisions replace participatory policy formulation. Tax compliance, in such a climate, becomes a source of anxiety rather than a civic duty. No wonder, then, that the country witnessed a nationwide shutter-down strike, not merely as a reaction to economic pressure, but as a collective indictment of the direction economic policy has taken.

In an exclusive conversation, Advocate Muhammad Ashraf Qamar, a tax law expert and former Income Tax Officer, criticized the government’s unilateral approach:

“Major legal changes in tax policy are made without engaging tax consultants, lawyers, or industry representatives. As a result, we get legislation that not only complicates the system but also imposes undue mental stress on taxpayers.”

He further noted that the 2025 income tax return draft, instead of simplifying compliance, is riddled with unnecessary complexities:

“Features like OTPs and QR codes might look modern on paper, but they alienate the very people they are meant to engage—particularly small traders who lack digital literacy. The return document should be foundational, not intimidating.”

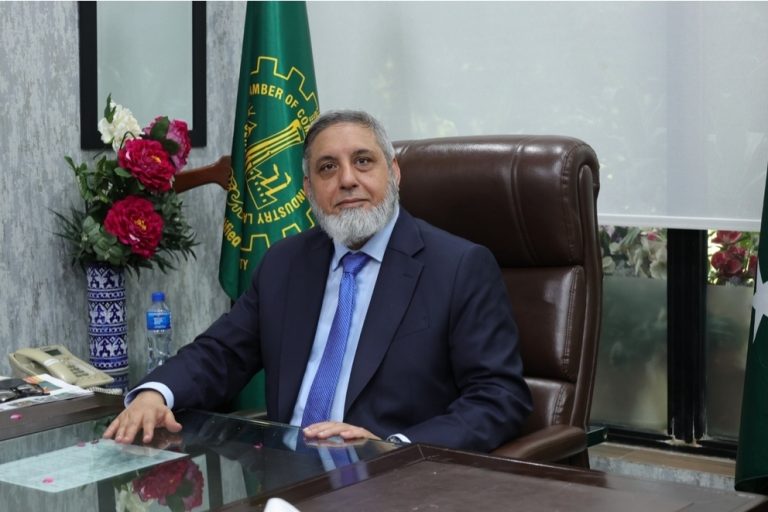

Speaking to this writer, Muhammad Ali Mian, former President of the Lahore Chamber of Commerce and Industry, pointed out that business leaders are united in their opposition to contentious sections like 37AA, 21(S), and 40B:

“The complete shutdown in both Karachi and Lahore—cities contributing over 60% to the national economy—should be a wake-up call for policymakers. Even smaller cities, though less visible, registered symbolic indoor protests.”

When asked about the government’s claim that the new return format offers “unprecedented ease” for businesses, Ali Mian was blunt:

“What kind of ‘ease’ involves giving the bureaucracy unbridled authority to arrest traders, raid offices, and disrupt operations on mere suspicion? Every major trade body—from the apex federation to local chambers—is protesting for a reason.”

He offered a more constructive way forward:

“We need an automated FBR system that eliminates direct contact between officials and taxpayers. Introduce a fixed-tax regime for small businesses. Reforms should build confidence, not fear.”

Raja Hassan Akhtar, founding chairman of the Independent Group in LCCI, echoed these concerns with urgency:

“No economy can grow in an atmosphere of fear. The government must immediately reassess any policy that spreads panic among traders. The Finance Act 2025 does exactly that.”

He argued for a shift in priorities:

“Before pushing new entrants into the tax net, ensure that those already complying aren’t driven away by harassment and uncertainty. Tax revenue will only grow when business owners feel safe, respected, and supported.”

Raja Hassan Akhtar stressed that policies should aim at expanding the tax base—not by burdening the old, but by encouraging the new:

“Instead of punishing existing taxpayers, focus on building confidence through trader-friendly, transparent policies. That’s the only way to foster long-term compliance and economic growth.”

Unless the government adopts a tax reform approach based on simplicity, fairness, and meaningful consultation, mistrust and resistance will continue to cloud its efforts. Policy making should not be an exercise in isolation; it must be a transparent conversation that leads to shared solutions. Only then can Pakistan hope to build an economy rooted in trust, participation, and sustainable development.